January 2017 activity report

Executive Director Catherine Girves joins staff and lay leaders at Summit on 16th United Methodst Church in celebration of Martin Luther King Jr's birthday at the Greater Columbus Convention Center.

Welcome to the monthly feature in which we round up all our events, earned media, program delivery, meetings and speaking engagements for the month. Representation and outreach like this is what you fund with your membership dollars and major gifts, folks! Behold, January:

Jan 3

Meeting with Elevator Brewery about Ride the Elevator and Bike the Cbus

Jan 4

Meeting with Whole Foods Easton about 2017's Year of Yay!

Regular meeting of MidOhio Regional Planning Commission's Citizen Advisory Council, which our Executive Director chairs

Jan 5

Meeting with Columbus City Schools regarding installation of new bike racks

Bike the Cbus planning meeting

Jan 9

Signage meeting of the Central Ohio Greenways Board

Jan 11

Team meeting at MurphyEpson regarding statewide Ohio Active Transportation Plan spring trainings

Jan 12

Conference call for Creating Healthy Communities about statewide trainings

Advisory Committee meeting for SR 161 Corridor Study

Ride of Silence planning meeting

Jan 13

Meeting at Ohio Department of Health to plan for the Ohio Active Transportation Action Institute Conference in June

Jan 14

Year of Yay! ride (cancelled)

Jan 16

Columbus' Martin Luther King Jr breakfast celebration, with leadership from Summit on 16th UMC, University Area Enrichment Association and University Area Freedom School

Yay Bikes! Board of Directors meeting

Jan 19

Meeting with leadership team of the Ohio Active Transportation Plan

Bike the Cbus planning meeting

Jan 24

Meeting with Ohio Department of Health and Center for Disease Control officials about Ohio's Active Transportation Plan

Jan 25

Regular meeting of the Central Ohio Greenways Board; presented on Miamisburg's Bike Friendly Business program

Jan 26

Ride of Silence planning meeting

Jan 27

Ohio Active Transportation Plan quarterly webinar; presented on our Ride Buddy program and Ohio's new 3' safe passing law

Jan 28

Attended Transit Columbus' board retreat as an invited guest

Jan 30

Canal Winchester City Council meeting; presenting with Kerstin Carr of the MidOhio Regional Planning Commission on the work of the Central Ohio Greenways Board

Jan 31

Attended the Active Transportation Engineering Conference in Columbus

Tracking (is) what matters

That fateful day, thanks to Deanne (front), a goal was born!

'From the Saddle' is a monthly note from our Executive Director.

On New Year’s Day 2016, I happened to be riding with a group of friends. We had ridden about 14 miles when my friend Deanne said we should ride 16, for 2016. It was cold and we wanted to be done, but we were so close, and it was such a good idea, that we pushed through and did it. There is something about setting a goal that helps a person make a plan, and then move towards achieving it—particularly in those moments when it is not very much fun. So that day I set a goal: I’d ride 100% of the days in 2016, even if only for very short trips, for a total of 2016 miles. Which changed everything about how I thought about bicycling.

One year later I can report the following: 255 days of biking (70%), for a total of 2,477 miles. Pretty kickass, no?!

I’m not gonna lie. There were days after I realized I wouldn’t make it to 100% in which I chose not to ride, all pouty-like. That’s a danger with setting big goals—when it seems you’ll not be able to attain them, it’s easy to say “f it” and quit. But because I’d been tracking, I noticed something. Maybe I wasn’t going to be able to 100% of days, but 70% was absolutely within reach…and still pretty kickass! Hmmm….so I got back on my bike and rode some more.

What gets measured gets done, as they say. Clichéd? OK sure. Still true? Yes!

I’m not hardcore. People seem to think I am, but I swear to you that I’m simply utilitarian (OK, and competitive….) I find life is easier when I choose to ride. It’s cheaper, of course, and also I don’t have to deal with parking. And I feel better about myself and the world around me. But I’m slow and my trips are often quite short. My point is that anyone can do what I’ve done—set a goal to ride a certain number of days or trips or miles, do it and then track it. The tracking is non-negotiable. Those of us who are up to something big must have a way to stay motivated, keep ourselves accountable, and cheer ourselves when we feel like a failure. We've almost always done more than we think we have, and knowing that can propel us to carry on.

Not coincidentally, given the time of year, we’re in the midst of setting 2017’s organizational goals at Yay Bikes!. For a small nonprofit, I’m proud to say that we are uniquely oriented toward evaluation. As we develop our measurable objectives and tracking protocols this year, we are motivated to identify the metrics that truly help us achieve the big goals that advance our mission. Not tracking for tracking’s sake, but tracking that provides access to excellence and transformation. From my own experience, I can tell you that this will get the job done. I'll be very excited to share our strategic plan with you as soon as it’s approved at our board meeting this month. In the meantime, you can check out our 2016 Annual Report (pdf) to see what we've accomplished recently!

For the record, what am I shooting for this year? I plan to ride 75% of days, and add more recreational miles to my total. Mileage isn’t so important to me because I’m about replacing car trips with bike trips, and those trips tend to be five miles or less. But whatever type of ride I’m on, you better believe I’ll be keeping track. Join me? Year of Yay! and Bike the Cbus do count, you know! :)

Riding with friends is the best way to ride. See you soon??

December 2016 activity report

Our Executive Director, Catherine (right), with Kimber Perfect of Mayor Ginther's office at the hearing for HB 154, Ohio's 3' safe passing law.

Welcome to the monthly feature in which we round up all our events, earned media, program delivery, meetings and speaking engagements for the month. Representation and outreach like this is what you fund with your membership dollars and major gifts, folks! Behold, December:

Dec 1

Columbus CEO: SIDs' Annual Meeting (pdf)

Dec 2

Statewide Mode Shift Project ("Your Move, Ohio") Meeting

Dec 3

Year of Yay! vetting ride

Dec 6

Attended hearing for HB154, Ohio's 3' passing law

Dec 7

(Bowling Green) Sentinel-Tribune: Complete Streets process to remain in place with closer eye on deadlines

Dec 10

Year of Yay! with 'Heartwarming' theme

Dec 14

Meeting with owner of Orbit City bike shop

Dec 16

(Bowling Green) Sentinel-Tribune: BG makes plans to align city budget

Dec 18

Received 7 bike racks for Columbus Public Health

Dec 19

COTA Project Advisory Group

Yay Bikes! board meeting

Govenor Kasich signs HB154, defining safe passing of cyclists in Ohio's as 3', into law; takes effect March 19

Dec 24

Meeting with founders of Steady Pedaling

'Heartwarming' ride recap

Thanks to ride leader Mark Spurgeon for a fantastic experience and this write-up!

Seventeen adventurous cyclists departed Whole Foods at Easton for the final Year of Yay! ride of 2016. Despite the 22 degree temperatures, smiles and good cheer were in evidence throughout the group. Perhaps it was Jeff Gove’s twinkling holiday lights that set the mood, or the anticipation of our stop at the Ohio Herb Education Center and Geroux Herb Gardens, a resource center in Gahanna—Ohio's Herb Capital (who knew!?).

Jeff Gove, festive as always! Photo credit: Michelle Blaney

The Nafzger-Miller house, in which the Herb Center is located, was a welcome respite at the halfway point on our 10-mile route. The house is on the National Register of Historical Places, but the more exciting thing about it to us that day was its holiday ambiance and, frankly, its well-functioning furnace! The Center was humming with activity, as little ones awaited their audience with Santa Claus, eager to share their holiday wish lists.

We peeked in but ultimately left Santa to the kids! Photo credit: Michelle Blaney

Learnin' all about HERBS! Photo credit: Michelle Blaney

Several riders took advantage of the close proximity of Bicycle One to fortify their winter-riding attire before embarking on the second leg of our ride. An unanticipated highlight of the final leg was the picturesque view along Olde Ridenour Rd, the park and golf course lightly dusted with snow, as we traveled north after departing Creekside Gahanna.

Among the more experienced riders were several novice and first-time Year of Yay! participants, myself included! This was a very congenial group, as the new riders were made to feel welcome and supported. Tips and tricks for beating the cold, and for making winter-riding pleasurable and safe were a favorite topic. Overheard were a number of spirited discussions about the merits of merino wool vs. lycra as we tackled some brief, but challenging sections on Granville St. and Morse Rd. Despite the freezing temperatures, and holiday shoppers in the throes of gift-giving fervor, the Heartwarming ride was deemed a success!

As usual, the crew enjoyed food & beverage aplenty at Whole Foods Market after the ride. Photo credit: Michelle Blaney

Here was our route: https://ridewithgps.com/routes/17929892

Evaluating a used bicycle

We are grateful to Keith "Lugs" Mayton for sharing his expertise in this guest blog post!

Keith atop his trusty steed. Photo credit: Keara Mayton

While a new bike might seem expensive, it's a worthwhile investment and relatively cheap in terms of hours of fun per dollar. When you buy new, support your local bike shops. If you can’t afford a new bike, at least buy your accessories from and have your bikes serviced at local shops.

If you simply can't afford something new, or just want to try explore bicycling before you commit, there are millions of good quality used bicycles in the U.S. that aren’t being ridden. Many of them eventually wind up posted for sale on Craigslist, social media, and the like, and some are a great value*. Here are some tips on figuring out whether a used bike is is worth purchasing.

First, when you are going to assess a used bicycle at a personal residence, ensure your personal safety. Take a buddy, look at bikes outdoors, etc. Use your common sense.

There are six basic things you'll want to examine in a used bicycle you are considering:

1) frameset, 2) wheels, 3) drivetrain, 4) brake system; 5) brand and 6) fit.

YOU WILL NEED TO TEST RIDE THE BIKE! UNLESS YOU ARE SAVVY, WALK AWAY FROM ANY BIKE YOU CANNOT TEST RIDE!

(*Editor's note: If an offer seems too good to be true, it very well may be. Stolen bikes are plentiful on Craigslist and some second-hand retailers—Once Ridden Bikes is a notable exception. Within Central Ohio, you may want to check Bike Snoop before you buy to see whether the bike you're considering has been posted.)

A beaut that Keith expertly salvaged. Photo credit: Keith Mayton

FRAMESET

Look at the frame from various angles to try to determine that tubes are straight and aligned. Head tube and seat tube should be parallel. Seat stays and fork blades should be symmetrical. Check whether forks are bent back or twisted.

Check frame for cracks, bulges, or significant dents. Cracks often form on the down tube just behind the head tube. A bulge in that location is often a sign of a front end collision and might be accompanied by fork blades that are bent back. Also inspect for cracks in the bottom bracket shell. Check the drive side chain stay for excessive "chain suck" damage.

The headset should turn smoothly and without play.

A little surface rust here and there is generally not a problem.

Ask to adjust the seatpost and stem. This allows you to adjust the bike for a test ride and also permits you to ensure the seatpost and stem are not stuck, i.e. chemically welded or rusted in place, 'cause that's bad!

When you test ride the bike, you should be able to ride the bike no hands in a straight line without leaning to either side. If you can't, there is probably a problem with alignment or improperly dished rear wheel.

WHEELS

Spin the wheels and observe where the rims pass the brake pads to make sure they are reasonably true (within 1–2mm) both vertically and horizontally. Also listen and feel for roughness in the hub bearings.

Even if the wheel is true, be sure to squeeze all of the spokes by pairs to see whether the tension on the spokes is even. Flick spokes with you fingernail—the tone should be pretty consistent. A true wheel with very loose and super tight spokes is probably almost dead.

Check rims for cracks. Also, feel the braking surface—if an aluminum rim is significantly concave on the braking surface the rim is near the end of its useful life.

Tire wear is, of course, normal. For old mountain bikes a great upgrade is inexpensive (think Kenda) semi-slick tires to replace knobbies for riding on the street. Makes a HUGE difference in reducing rolling resistance.

DRIVETRAIN

The drivetrain should shift relatively smoothly. Look for bent, broken, or missing parts (to the extent you know what to look for).

Check cables and housings. Frayed ends are common. Fraying behind derailleur anchor bolts or cable stops probably requires replacement. Cable housings that are rusty, that lack outer casing, or have acute bends will also need to be replaced.

Replacement of a chain is almost a given so a dirty or somewhat rusty chain might not be a deal killer.

Check the chainrings while the crank is turning to see whether they spin true. Inspect the crankarms to make sure they are not bent or cracked. Check to make sure pedals are threaded in straight—otherwise they might be cross threaded, which might mean the crank arms would need to be re-tapped or replaced. Also examine the teeth on the chainrings for wear. Teeth that are worn out look hooked or like shark fins.

Grab both crankarms and pull back and forth sideways. Excessive play could indicate one of several possible problems. Pedals should spin relatively smoothly. Check plastic pedals for signs of cracks.

BRAKE SYSTEM

Brakes should operate relatively smoothly and, yes, cause the moving bike to stop safely. Make sure the brakes "return" after the levers are released. Failure to return indicates corroded cables/housings or weak, improperly adjusted, or brake broken springs. Inspect brakes and levers to see whether they are bent, cracked, or appear to be missing any pieces.

Check cables and housing as with drivetrain.

Brake pads wear and might need replacement. It's a good thing to upgrade them regardless.

BRANDS

I would avoid Pacific, Magna, Kent, Mongoose, Huffy, Columbia, and any brand sold at big box stores.

Fuji, Panasonic, Bridgestone, Miyata, Nishiki, Univega, Trek, Giant, Specialized, and brands sold at reputable bike shops are generally good quality bikes. Really, most bicycles that were made in Japan or Taiwan from the 1970s through the 1990s tend to be pretty good, or at least not horrible.

Schwinn, Ross, and Free Spirit are a mixed bag. The lugged steel bikes of all 3 brands are generally good. The old electro-forged Schwinns like the Varsity, Continental, Collegiate, and Suburban were not horrible bikes but they are far heavier than necessary, as in about 40 pounds. Also, Schwinn now makes a line of bikes sold at big box stores. I would avoid those. Ross made cheap gas pipe bikes, easy to spot because they lack lugs and have one piece steel cranksets. Similarly, there are a few Free Spirit models that were made in Austria by Puch that are good. The good ones have lugged construction.

Older French and British bikes like Peugeot, Motobecane, Gitane, and Raleigh might not be a good choice unless you have some basic mechanical skills or a willingness to learn them. Weird threads, cottered cranks, and plastic Simplex derailleurs on the lower end models can make working on them a little more challenging. But when they are properly serviced and adjusted they can be good bikes. By the late 1970s, Raleigh and some European brands began having their bikes made in Japan and eventually Taiwan. I feel that the quality of these later bikes is generally higher.

It never hurts to do a little research on the brand and model before you go look at a bike. The catalogs of many of the major brands are posted in various places on the internet. For example, Waterford Precision has catalogs from before Schwinn went bankrupt. Sheldon Brown’s site has a lot of the old Raleigh catalogs.

If you want some basis for determining a fair price, I find it useful to search eBay completed auctions. Ignore ongoing auctions since bikes often eventually sell for far less than a “buy it now” price, and some sellers tenaciously relist bikes at inflated prices. Also, in my opinion, bikes sold locally should sell for roughly two-thirds of completed sales on eBay because eBay auctions reach the worldwide market for used bikes, which includes well heeled collectors.

FIT

Notions abound concerning how properly to determine whether a bike fits, and rules of thumb have changed significantly over the years. Also, principles of bike fit that might work well for someone who’s racing on a drop bar road or cyclocross bike may have little applicability to someone looking for a city bike with swept back bars and an upright riding position. So for purposes of this article, I’m going to boil it down to a few basic criteria. First, is the bike sufficiently comfortable when you test ride it? The seller should be willing to raise or lower the saddle or stem to help you figure this out. Obviously you should be able to achieve sufficient leg extension without extending the seatpost above maximum height. Also notice whether you feel either too stretched out or too cramped as a result of the distance between the saddle and the handlebars. In addition, are you comfortable with how the bike steers and handles? Last, regardless of the above, there should be at least an inch of space between your crotch and the top bar when you straddle the bike. Here's a helpful video that shows what this might look like for you:

Good luck with your search, and have fun!

Bowling Green: a case in point

The Bowling Green fire chief takes a turn Photo credit J.D. Pooley of the Sentinel-Tribune

I spent 23 hours in Bowling Green this fall. On October 12 Kathleen Watkins and I led a Professional Development Ride with the City Engineer, Fire Chief, Civil Engineer and Assistant Municipal Administrator. I returned November 7 and hosted two Professional Development Rides with the Director of Public Works, 2 City Council members, a Bowling Green University student organization representative, a reporter from BG Independent News and one from the Sentinel-Tribune, 2 City Council Members, Ohio Department of Transportation District 2 Engineer and 2 local bicycle advocates. After the rides that day, I led a public meeting with approximately 50 attendees in which I presented about safe riding practices and facilitated discussion about them. The media coverage was encouraging:

Bike tour of BG opens eyes to some solutions

Cycling advocacy group shows ‘tourists’ how to experience bike-friendly BG

VIDEO: Advocacy group's tour points out safe ways to bike BG

And the direct feedback (from the ODOT engineer) was even more so:

“I participated in the Bowling Green Professional Development Ride yesterday afternoon. I can’t begin to tell you how much I learned from Yay Bikes! about bicycling in this community in just over 3 hours.

Although I have lived in Bowling Green for the past 14 years, I have never ridden a bike here prior to yesterday. I am not a cyclist. I don’t own a bicycle, and I haven’t ridden one for 30 years. Yay Bikes! provided me with a bike and helmet for yesterday’s ride.

The ride was not at all what I expected it to be. I fully expected a high-pressure sales pitch to construct miles of bike lanes and multi-use paths all over the city. Instead, the entire experience and information shared was intensely practical and focused on cost-effective solutions. The experiential nature of the session really opened my eyes to a lot of things which impact bicyclists and traffic safety that I would likely neglect otherwise, such as: trees, sidewalks, pavement widths, lane widths, use of signaling to turn/change lanes, and (most importantly) bicyclist lane position.

I was pleasantly surprised how courteous vehicular traffic interacted with us on every street we traveled. We rode on several residential, collector and arterial streets, including significant stretches along State Route 25 (Main Street), a 4-lane arterial with many signalized intersections and driveways. We did not have a single close call; no one honked, yelled, or made offensive gestures at us the entire time we were on the road.

I highly recommend this program to anyone who wants to make their community more bicycle-friendly. It was an eye-opener for me, and I’m sure that others will have a similar positive experience.

”

Photo credit: Kathleen Watkins

Since the rides, I've spent at least 7 hours on the phone with city leadership, including Jason Sisco, Bowling Green's City Engineer, and Robert McOmber, a City Council Member, about updates they're considering. A group from Bowling Green is planning a trip to Columbus to experience our infrastructure first-hand. And soon, "Bikes May Use Full Lane" signs will be popping up throughout town (the message is already in rotation on the electronic billboard by the police station)!

So 47 hours—23 in Bowling Green, 7 on the phone with their leadership, and an additional 17 in the office preparing. And yet a complete transformation is underway in that community, with dozens of advocates and professionals now on a coordinated path to accommodating people who ride there. Wouldn't it be perfection if everyone in America had an experience of riding on roads? Wouldn't it be pretty close to perfection if every transportation professional did? We're back in action on another round of ODOT-funded Professional Development Rides next spring. Support that work now with your gift.

November 2016 activity report

Executive Director Catherine Girves represents on a panel at the Center for Urban & Regional Analysis' Healthy Places: Designing Cities for Biking and Walking forum.

Welcome to the monthly feature in which we round up all our events, earned media, program delivery, meetings and speaking engagements for the month. Representation and outreach like this is what you fund with your membership dollars and major gifts, folks! Behold, November:

November 2

2 Professional Development Rides in Akron

November 5

Yay Valet! @ OSU v Nebraska

November 7

2 Professional Development Rides in Bowling Green

Sentinel-Tribune: "Cycling advocacy group shows 'tourists' how to experience bike friendly BG"

Sentinel-Tribune: "Advocacy group's tour points out safe ways to bike BG"

BG Independent News: "Bike tour of BG opens eyes to some solutions"

November 10

Columbus Green Team meeting

Tabling at Columbus' Downtown SID Annual Meeting

November 12

Year of Yay! featuring "Folklore" theme

Meeting with Bowling Green City Council Member Robert McOmber

November 13

Meeting with Bowling Green City Engineer Jason Sisco

November 16

Community Shares of Mid Ohio meeting

November 17

Meeting with Megan Melby of Columbia Gas and NiSource employees

November 18

Meeting with Columbus City Schools about bike parking

Presenting on the CURA panel Healthy Places: Designing Cities for Biking and Walking (with Gulsah Akar, Kerstin Carr, Scott Ulrich, Harvey Miller)

November 20

Year of Yay! ride leader training

November 21

Yay Bikes! board meeting

November 22

Ohio Active Transportation Planning Group lead meeting

November 26

Yay Valet! @ OSU v Michigan

November 28

MORPC Community Advisory Council meeting

November 29

Central Ohio Greenways board Signage and Wayfinding Committee meeting

November 30

Volunteer appreciation event

Gratitude

Profound gratitude.

November! The season to reflect and give thanks!

Conveniently, with all the hours I've clocked driving across Ohio delivering Professional Development Rides of late, I've had plenty of time to reflect (when I'm not rocking out to Hamilton at top volume, duh). And it turns out I'm grateful, fundamentally.

Of course my gratitude extends far beyond the scope of this blog post, so in keeping solely with the context of my current situation... For weeks now, as you may know, I've been delivering Professional Development Rides at a rate of 1, 2 or even 3 (!) a week. To date Yay Bikes! has led 20 rides with approximately 100 professionals; 5 more are scheduled and ODOT has just renewed our contract to provide an additional 21 rides. By spring, more than 200 professionals in more than 2 dozen communities in Ohio will have ridden with us. Many of them will have experienced their community by bicycle for the very first time on their ride.

So when I think of what I'm grateful for this season, foremost on my list is all those who have ridden with us. These people! You guys—I don't wanna say this too plainly lest the word gets out, but....{whisper} they don't have to ride with us! They can easily fill their time with whatever legions of VIP tasks no doubt piling up on their desks. I mean, we have mayors and police chiefs and city engineers and economic development officers and city council members and more coming on these rides! These positions are excuses. Add in the fact that bicycle advocates don't have the best reputation (pugnacity: it's true) and that they may be terrified of riding with traffic, and it's a darn near miracle that anyone rides with us at all.

But their commitment to this work is unexpected and humbling and inspiring, and they do ride. I'm privileged to be granted their trust, and the ability to inform open minds as they consider how best to encourage bicycling in their communities. It is a rare gift from the universe, and I give thanks.

Join Yay Bikes! today to join me in celebration of this work!

Riding with some Athens VIPs. Yay you!

October 2016 activity report

Franklin County Consortium for Good Government's candidate forum, presented in partnership with DRAC and Yay Bikes! Photo credit: Bob Bickis

Welcome to the monthly feature in which we round up all our events, earned media, program delivery, meetings and speaking engagements for the month. Representation and outreach like this is what you fund with your membership dollars and major gifts, folks! Behold, October:

October 1

Yay Valet! @ OSU v Rutgers

October 3

Vetting the Massillon Professional Development Ride with help from local cyclists

Ride of Silence happy hour fundraiser at Hills Market Downtown

October 4

Attended the MORPC Community Advisory Committee meeting

October 5

Bike the Cbus planning meeting

Vetting the Troy Professional Development Ride with help from local cyclists

October 6

Troy Professional Development Rides (2)

October 7

Massillon Professional Development Ride

October 8

Year of Yay!, "The 70s" theme

Yay Valet! @ OSU v Indiana

October 10

Vetting the Bowling Green Professional Development Ride with help from local cyclists

October 11

Vetting the Athens Professional Development Ride with help from Yay Bikes! members

October 12

Bowling Green Professional Development Ride

Conversation with Columbus City Schools to help plan for bike racks outside schools

October 13

Meeting with Lucky's Market to explore potential partnership opportunities

October 14

Vetting the Athens Professional Development Ride with help from local cyclists

October 16

Yay Valet! @ Columbus Marathon

October 17

Westerville Professional Development Ride

Yay Bikes! board meeting

October 18

Athens Professional Development Rides (2)

Attended the Annual Race Event Meeting with Columbus Police Department, Columbus Recreation and Parks and the Division of Fire

October 19

Met with a Capital University student about creating a video highlighting our Professional Development Rides

Presented the 2016 Candidates Forum with the Franklin County Consortium for Good Government, in partnership with DRAC

October 20

Vetting the Nelsonville Professional Development Ride with help from Yay Bikes! members

October 21–22

Volunteering @ Highball Halloween to raise funds for Ride of Silence

October 22

Presented on transportation bicycling at the NeighborWorks Community Learning Institute National Conference

October 25

Nelsonville Professional Development Ride

October 26

Meeting of the Central Ohio Greenways board, on which our ED serves

October 28

Vetting the ODOT District 8 Professional Development Ride with local cyclists

Bike the Cbus planning meeting

CURA (The Center for Urban and Regional Analysis at OSU) Community Bike Roundtable

October 29

Yay Valet! @ OSU v Northwestern

October 30

Year of Yay! Ride Leader Training

October 31

ODOT District 8 Professional Development Ride

'The 70s' ride recap

Thanks to ride leader Grant Summers for a fantastic experience and this write-up!

October’s “70s ride” was a great ride punctuated with 3 unique stops that our group really enjoyed! It was the first ride that I have led since joining Yay Bikes! last year, and it was also the first ride since Fall started. We were greeted with a cool, sunny morning, and our route covered approximately 21 miles.

Someone was READY for this one!

After leaving the Whole Foods at Easton, we rolled east through through several Northeast Columbus neighborhoods until we arrived at our first stop, Musicol Recording. This record studio, at its current location on Oakland Park since 1971, also features a vinyl pressing operation in the basement. It is one of only two businesses currently in Ohio that press vinyl records. Warren Hull graciously gave our group a tour of the recording studio, cozily packed with analog recording equipment and instruments, and the vinyl pressing area. We had a lot of fun at this stop!

And just like that, a new supergroup was formed!

Our next was was only a short three mile ride north, mostly on Maize road, until we reached Skate Zone 71, which you can see off I-71. Dan Merzke, the operations manager, greeted our group and gave us a brief tour of this skating rink plus a rundown of the various skating sessions they hold. Perhaps we might have a Yay Bikes! Adult Skate party here?!?!?

Operations Manager Dan Merzke shares about Skate Zone 71. Photo credit: Darrell McGrath

From Skate Zone 71, we rode northeast through the winding, tree lined streets of the Forest Park neighborhood, until we reached our final stop, Starbase Columbus. The staff was excited to see our group! Each of our riders received a bag with some snacks, and Lori told us stories about meeting the actors/actresses involved with Star Trek. She also demonstrated some Star Trek themed toys, such as a Bluetooth communicator, and a remote control fashioned to like like a phaser. This was quite a memorable stop.

After that it was time to head back to our home base. We were able to pick up the Alum Creek Multi-Use trail at James Casto Park, which is near the Alum Creek shopping center off route 3. We rode this trail until we reached the Strawberry Farms neighborhood. From their it was a short uphill incline until we safely reached Sunbury Road and eventually Whole Foods.

I want to thank each of our hosts for taking the time to speak with us during this ride.

Happy Cycling…………

Seeking 2017's Year of Yay! button artist

Five years of Year of Yay! buttons by local artists Ryan Brinkerhoff (2012), Rich Schneider (2013) Jessica Seyfang (2014). Devin Carothers (2015) and Thom Glick (2016).

Year of Yay! is 12 monthly rides that each feature a unique theme—which could be something tangible like "Chocolate", or more abstract, like "Resilience". All 12 rides provide participants with a 1.25" button that reflects the theme and connects it somehow to bicycling.

We are now accepting applications for a button artist to design the 2017 Year of Yay! ride buttons. This is a paid gig! All styles are welcome! To apply, design one button on the theme "Organized Labor" and submit a jpg, png, eps or pdf version of the image to Meredith by October 26. A decision will be made by October 31; all buttons will be due by January 1.

We look forward to seeing your creativity in action!

One bike ride at a time

Sandusky's Professional Development Ride.

“I thought we would focus on getting bikes off of streets, but the ride made me think of biking in a different way and that done right, you could ride almost anywhere.”

This month I've been criss-crossing our great state of Ohio with fellow Yay Bikes! ride leaders, guiding dozens (77 and counting!) of "influencers" on Professional Development Rides that are transforming how they think about bicyclists and bicycle infrastructure. That's not my own feel-good impression. It's coming through loud and clear, over and over again, on our program evaluation surveys. You can see it in participants' own words, scattered throughout this post: this work works.

Where we've ridden.

By the end of this month we will have ridden in 13 communities with professionals from all over Ohio. Mayors! Council Members and Commissioners! Engineers! Planners! Advocates! Public health and parks employees! Philanthropists! Economic development officers! Etc.!

“Our instructors were excellent! The experience has positively changed my thoughts on cycling and bicycle enthusiasts.”

Why do all these VIPs consent to ride with Yay Bikes!? It's "the Yay Way"—or rather, how we are with them: kind, encouraging, neutral, grateful. Quoting one hesitant participant: "This isn't going to be some extended bitchfest, is it?". No, it isn't! We don't attack, we don't proscribe, we don't bitch. We lead and teach, and allow our participants to reach their own professional conclusions about what would work best for their communities' cyclists, given their unique circumstances.

“I was unaware of how much right to the traveled lane roadway bike users had.”

Many of these professionals had never ridden streets before, or didn't understand how to ride them in a way that maximizes their safety. With the best of intentions, they simply didn't know what they didn't know about how a cyclist experiences different roads, or makes the choices they do to stay safe. But six weeks after their rides? A significant majority say they now "advocate more strongly and confidently for bicyclists" at their jobs. Wow. Take a pause here to think about that. People in position to influence conditions for cyclists throughout the state understand now what cyclists need AND they have become bicycle advocates! This. Work. Works.

“I learned the viewpoint of the cyclist. I learned traffic laws. Misconceptions were cleared up.”

Constant travel is exhausting. My unanswered emails are piled a mile high; my brain is mush. But according to the data, one thing remains true and steady: Yay Bikes! is making a difference in this world. And that brings me joy and peace during this crazy season. Which I look forward to sharing with you.... next month, after a nap or several...

We offer programming like this with support from the Ohio Department of Health, the Ohio Department of Transportation and the support of our members. Join now!

We're hiring!

Kathleen says: "We're alright! Join us! " Photo credit: Ben Ko

Yay Bikes! is pleased to announce that we are hiring for the position of Program Coordinator! Here's how to apply:

- Review the job description and email Kathleen with a cover letter and resume by Friday, October 21.

- Yay Bikes! will invite qualified applicants to interview during the week of Oct 31.

- A hiring decision will be made in November; the position begins January 2017.

Contact Catherine with any questions about this position or the hiring process.

September 2016 activity report

Officials in Sandusky, Ohio on a Professional Development Ride. Photo credit: MJ Reed

Welcome to the monthly feature in which we round up all our events, earned media, program delivery, meetings and speaking engagements for the month. Representation and outreach like this is what you fund with your membership dollars and major gifts, folks! Behold, September:

September 1

Bike the Cbus planning meeting

Columbus Underground: City Phasing Out “Share the Road” Signs

September 2

Bike the Cbus on-site registration & raffle

ABC 6 On Your Side: City changing bicycle awareness signs

September 3

Yay Valet! @ OSU v Bowling Green and Bike the Cbus

road.cc: US city to replace 'share the road' signs with 'bikes may use full lane' ones

September 5

Yay Valet @ Upper Arlington Labor Day Arts Festival

September 7

Vetting the Powell Professional Development Ride with help from Yay Bikes! members

Next City: City to Replace "Share the Road" Signs With a Clearer Message

September 8

Troy Professional Development Ride, in Columbus, with their City Engineer and others

September 10

Year of Yay! with "Resilience" theme

September 12

Powell Professional Development Ride

September 13

Vetting the Richland County Professional Development Ride with help from Yay Bikes! members and local advocates

September 15

Vetting the Miamisburg Professional Development Ride with help from local cyclists

September 16

Miamisburg Professional Development Ride

September 19

Richland County Professional Development Rides (2)

Bicycling Magazine: The 50 Best Bike Cities of 2016 (We're 39! We're 39!)

September 21

Vetting the Fremont Professional Development Ride with help from local cyclists

Vetting Tour de Brew with the team of leads and sweeps

September 22

Fremont Professional Development Ride

Tour de Brew planning meeting

September 23

Meeting with Zach Traxler to discuss the possibility of launching an online store

September 24

Tour de Brew fundraising ride in partnership with Water for Good to provide clean water for communities of Central Africa

September 26

Vetting the Sandusky Professional Development Ride with help from local cyclists

September 27

Fremont and Sandusky Professional Development Rides

September 28

Vetting Columbus ride for private transportation consultants

September 29

Professional Development Ride, in Columbus, for transportation professionals designing roads nationally

Meeting with Sidney Hargrow, Executive Director at Community Foundation of South Jersey, to discuss philanthropy

'Resilience' ride recap

Thanks to ride leader Kathleen Koechlin for a fantastic experience and this write-up!

On the eve of the 15th anniversary of the September 11, 2001 tragedy, 34 cyclists set out to honor those people and things that exemplify resilience. To get to our first stop, the Somali Community Association of Ohio (SCAO), we climbed what the ride leader, Kathleen Koechlin, likes to call the “super-secret trail” which links the Alum Creek trail with the neighborhood of North Linden. It was a challenging uphill climb, but it is a good trail to know if you ever want to commute to Easton or anywhere along the Alum Creek Trail from the Clintonville or North Linden neighborhoods. When we arrived at the first stop, our speaker was nowhere to be found, so Kathleen talked with the group about the meaning of the word “resilience” and why the SCAO was included in the ride. She also provided some details about the Somali population in Columbus and the life that they had fled.

Ride leader Kathleen Koechlin talks with the group about the resilience of Somali refugees. Photo credit: Darrell McGrath

Next we headed north to Westerville’s First Responder Park where we were met by Tom Ullom, retired firefighter and founder of the park. He had set up an amazing display of 9/11 artifacts which included photos of all the firefighters lost on that horrific day 15 years ago. Tom described his friend and inspiration for the park, fallen firefighter Dave Theisen whose memory is honored at this site with a sculpture called "The Crossing", designed by Steve Geddes and Bob Moore. He then gave the account of how the piece of World Trade Center (WTC) Steel, known as C-40, came to find a home in Westerville. You can hear his full presentation here.

Tom Ullom, retired firefighter and founder of Westerville’s First Responder Park, shares how a piece of the World Trade Center made its way to Central Ohio. Photo credit: Napoleon Allen

Steel from the World Trade Center. Photo credit: Catherine Girves

A photo op stop at Otterbein University on the way to the third stop. Photo credit: Darrell McGrath

We wound our way through the beautiful streets of Westerville to reach our third and final stop, Inniswood Metro Gardens. There, Cindy Maravich, Senior Environmental Educator, took us into the gardens to sit in a beautiful shaded area outside of what used to be Grace and Mary Innis’s home. She told the story of the sisters who left their home and grounds to the Columbus Metro Parks upon their deaths. She talked about the resiliency of some of the insects and plants in the park and told of the types of wildlife one might see when walking the nearly 2 miles of trails. She even gave us stickers!

Some of the group opted to hang out under the shade of a tree while others ventured into the gardens. Photo credit: Keith Lugs

Entertaining ourselves with bike helmet bunny ears while waiting to turn onto Morse Road and then into the Whole Foods parking lot at Easton. Photo credit: Darrell McGrath

Finally, we headed back to Easton through the neighborhood known as Strawberry Farms, another good discovery for getting around this area of town by bicycle. The spirit was lite, even as we ended our 22 mile, somewhat hilly ride. It was a great day!

Influencing the influencers

MORPC region professionals! Photo credit: Kerstin Carr

When Yay Bikes! works to advance our mission, we are guided by the powerful and uniquely clear theory of change we've developed over the years. We've taken to calling it "The Yay Way!", and it's pretty much omnipresent within our organization. What's perhaps lesser known is through whom we enact our vision for a bike friendly world—or, rather, the primary audiences we believe can help us effect change. There are two: 1) those who want to ride now, whether they are cyclists or still bike curious, without waiting on bicycle-specific street infrastructure and 2) the professionals who are in a position to influence the conditions cyclists encounter when they ride. And I'm happy to report that we've recently had occasion to impact both groups statewide, courtesy the Ohio Department of Transportation and the Ohio Department of Health. And I'm even more happy to report that there's a way you can be involved in this work (scroll to the bottom of this post to learn more)!

RIDE BUDDY TRAINING

August 23–25 we hosted 10 bicycle advocates from around the state (representing Richland County, Athens, Akron and Stark County in addition to Columbus) at a training designed to provide them the skills to design and lead How We Roll and Ride Buddy–style rides, a la The Yay Way! These intrepid souls spent much of their 2.5-day training on the road, creating and riding routes and practicing their scripts. They'll now be taking what they learned back into their communities to teach others how to ride roads for their everyday travel!

A group of trainees from around the state learn how to deliver Ride Buddy and How We Roll rides. Photo credit: Meredith Erlewine

PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT RIDES

So far, transportation, parks, health, utilities, economic development, elected officials, law enforcement and planning professionals from numerous communities—Zanesville, Worthington, Troy, Columbus, Miamisburg, Westerville, Powell/Liberty Township, Bexley, Gahanna, Reynoldsburg, Mansfield/Richland County and Fremont, among others—are riding with us to understand how they can better accommodate people who ride for transportation. On routes we create, with help from our members, that showcase the good, bad and ugly of riding in their communities, they get to experience their streets from the perspective of a cyclist. And because they really want to design bike friendly communities and just aren't sure quite what they don't know they don't know, these rides literally transform how people understand their jobs.

The cool part? You can be involved in this part of our work. (scroll, scroll, scroll)

Zanesville professionals! Photo credit: David Curran

Worthington professionals! Photo credit: Meredith Joy

We invite anyone who's a Yay Bikes! member to provide input to the rides we deliver to transportation professionals. What works for cyclists there? What doesn't? What would you love for the people who design your roads to understand? On vetting rides before each professional development ride with the professionals, we invite members to provide input.

Why members only? Well, because we carefully solicit and curate all input, and invest a lot of staff time in that process. We're happy to do it—it is, in fact, a critical element in our effectiveness—but it's definitely an investment we make in service of people who are demonstrably committed to this work. So join today! We are likely coming to your community soon, and you'll wanna be ready to roll with us!

August 2016 activity report

Leading a professional development ride for City of Worthington engineers, parks and utilities staff.

Welcome to the monthly feature in which we round up all our events, earned media, program delivery, meetings and speaking engagements for the month. Representation and outreach like this is what you fund with your membership dollars and major gifts, folks! Behold, August:

August 1

Meeting with Tyler Steele of the Major Taylors regarding Bike the Cbus

Meeting with James Young, Columbus City Engineer, regarding our joint American Public Works conference presentation

August 2

Board meeting of Franklin County Consortium for Good Government, on which our Executive Directo serves

August 4

Travel to Zanesville to vet their Professional Development Ride

Bike the Cbus planning meeting

August 6

Year of Yay! vetting ride

August 10

Columbus Alive: "Wheels of Fortunate"

August 11

Regular meeting of the City of Columbus Green Team Working Group Chairs, which our Executive Director chairs

Regular meeting of the City of Columbus Green Team, which our Executive Director chairs

Meeting of the statewide Ride Buddy training team

August 12

City of Zanesville Professional Development Ride

August 13

Year of Yay!, Local Food theme

August 14

Bike the Cbus and Bike the Cbus+ vetting rides

Bike the Cbus+ ride lead/sweep training

August 17

Regular meeting of the DRAC board, on which our Executive Director serves

August 19

Travel to Worthington to vet their Professional Development Ride

August 20

Yay Valet! @ Grove City EcoFest

August 23

City of Worthington Professional Development Ride

Regular meeting of the CoGo Bike Share Advisory Board, on which our Executive Director serves

August 23–25

Delivered Ride Buddy training for professionals from around the state

August 26

Attended the Regional Trails Summit in Cincinnati, at which Board Member Brian Laliberte presented on the keynote panel "Balancing the Active Transportation Network"

August 27–30

Attended the PWX 2016: The American Public Works Association Conference in Minneapolis, at which our Executive Director Catherine Girves presented on "Municipal Engineers and Bicycle Advocates Make Really Great Friends!"

Minneapolis Bike Hub meeting

Dero facility tour

AAA Ohio now covers cyclists!

Updated Dec 2017, check AAA for the most current information.

Yay Bikes! thanks AAA Ohio Auto Club for this guest blog post about their new service!

Did you know you are now covered on your bicycle with AAA membership?

For more than 100 years, AAA has been providing world-class automobile emergency roadside assistance—and it still does. But as new forms of transportation become increasingly popular, AAA is reinventing what roadside assistance means, providing you safety, security and peace of mind when on the road on four or two wheels!

Does this service cost extra?

No! Bicycle Breakdown Service is automatically included with a AAA Ohio Auto Club Membership. There is no additional sign-up or enrollment, and coverage is included on all levels of Membership.

Members can use any of their yearly service calls for Bicycle Breakdown Service. The bicycle towing mileage works the same as vehicle towing mileage: Classic = 3 miles, Plus = 100 miles, Premier = 100 miles and one 200-mile tow. Long distance cyclists may want to upgrade their membership to Plus or Premier to ensure they can access help no matter where they ride! Additional family members can be added to a primary membership for as low as $35/year.

What other benefits can cyclists receive through AAA?

AAA has partnered with a variety of bicycle shops to provide members with discounts on all their biking needs. Find a full list by visiting AAA.com/Bicycle.

How do I use AAA's Bicycle Breakdown Service?

To get help, call 1.888.AAA.OHIO (222-6446) and request a bicycle tow. Make your way to the nearest accessible road and a service vehicle will arrive to take you and your bicycle where you would like to go. If you are biking with friends or family, service vehicles may transport as many people as there are seat belts. AAA will help you find alternative transportation for other riders.

Where can I access the Bicycle Breakdown Service?

AAA Ohio Auto Club partnered with AAA Club Alliance in 2017 to expand the Bicycle Breakdown Service area into the counties colored blue on the map. The majority of Ohio is now covered!

Learn more about this program by visiting AAA.com/Bicycle.

'Local Food' ride recap

Thanks to ride leader Alec Fleschner for a fantastic experience and this write-up!

Gathering pre-ride at Whole Foods Market Easton. Photo credit: Shyra Allen

This month’s ride, “Local Food,” was incredible! The weather was hot, but the route wasn’t too hilly, and each stop helped refuel us for the next leg. We had over 45 riders registered, and the route went just a hair over 23 miles. The weather predictions said that rain would be coming, but it held off until after the ride. Beautiful weather!

Nothing but sunshine! Photo credit: Shyra Allen

Starting from Whole Foods in Easton, we traveled to the south side of the airport and over to the Columbus Produce Terminal to meet with Jeff Givens of Sanfilipo Produce. He spoke for a couple of minutes on how the company has been providing produce to Columbus businesses and people since 1899, but he gave us lots of time to check out the Cash & Carry store. He also kindly provided us with bags with grapes and apples. Thank you so much!

Ready to explore Sanfillipo Produce. Photo credit: Alec Fleschner

Jeff introduces Sanfillipo to us. Photo credit: Shyra Allen

Look at those goodies! Photo credit: Alec Fleschner

After that, we headed north through Gahanna on our way to Coffee Time Bakery and Cafe. Check out Darrell McGrath's video of us riding down Bridgeway Ave:

At Coffee Time, we fueled up on sweet treats and coffee, as well as looking around at their baking supplies, scoping out the candy shop, and just relaxing for a few minutes before we took off.

Nothing like a coffee break at the halfway point! Photo credit: Shyra Allen

Checker break? Don't mind if we do! Photo credit: Shyra Allen

Finally, we headed to Nazareth Restaurant & Deli. The owner, Hany Baransi, was considering leaving the business after a man wielding a machete attacked patrons in February of this year, making national news. However, he has remained and recently remodeled. He was kind enough to talk to us about his food and provide us samples of hoummus and baba ghannoug, along with fresh pitas for dipping.

Owner Hany Baransi explains the appeal of hoummus and baba ghannoug to us. His samples help just as much! Photo credit: Shyra Allen

Lining up to try the food. Photo credit: Alec Fleschner

Our bikes laden with food, we headed back to Whole Foods. Thank you to everyone who rode with us! We hope to see you next month!

Biking the Cbus

Riders in Year 1, way back in 2008.

We've got a great little ride the Saturday of Labor Day weekend, perhaps you've heard of it—Bike the Cbus? Well, whether you have or have not, there are at least a few things you don't know about this gem of an experience. And there is so much to be excited about as we unveil new elements for this year's ride:

Big Reveal #1 NEW START and END location!!!! Each year our riders find fantastic places they did not know existed. Discovering something new on a ride is great. Taking time to explore a new place over lunch with bike friends is even better. So we've decide to move the start and end of Bike the Cbus around Columbus to do just that. We start this traveling treasure hunt with one of our biggest supporters Elevator Brewing Co. 13th Floor Taproom. The Elevator Brewing Company was founded in 1999 by a Father/Son drinking team committed to delivering quality craft beer to authentic people. Riders have the opportunity to wander around the brewery post ride to see the big tanks in action.

Lunch will again be provided as part of registration from one of multiple food truck vendors. And, yes, the taproom will be open for business post ride.

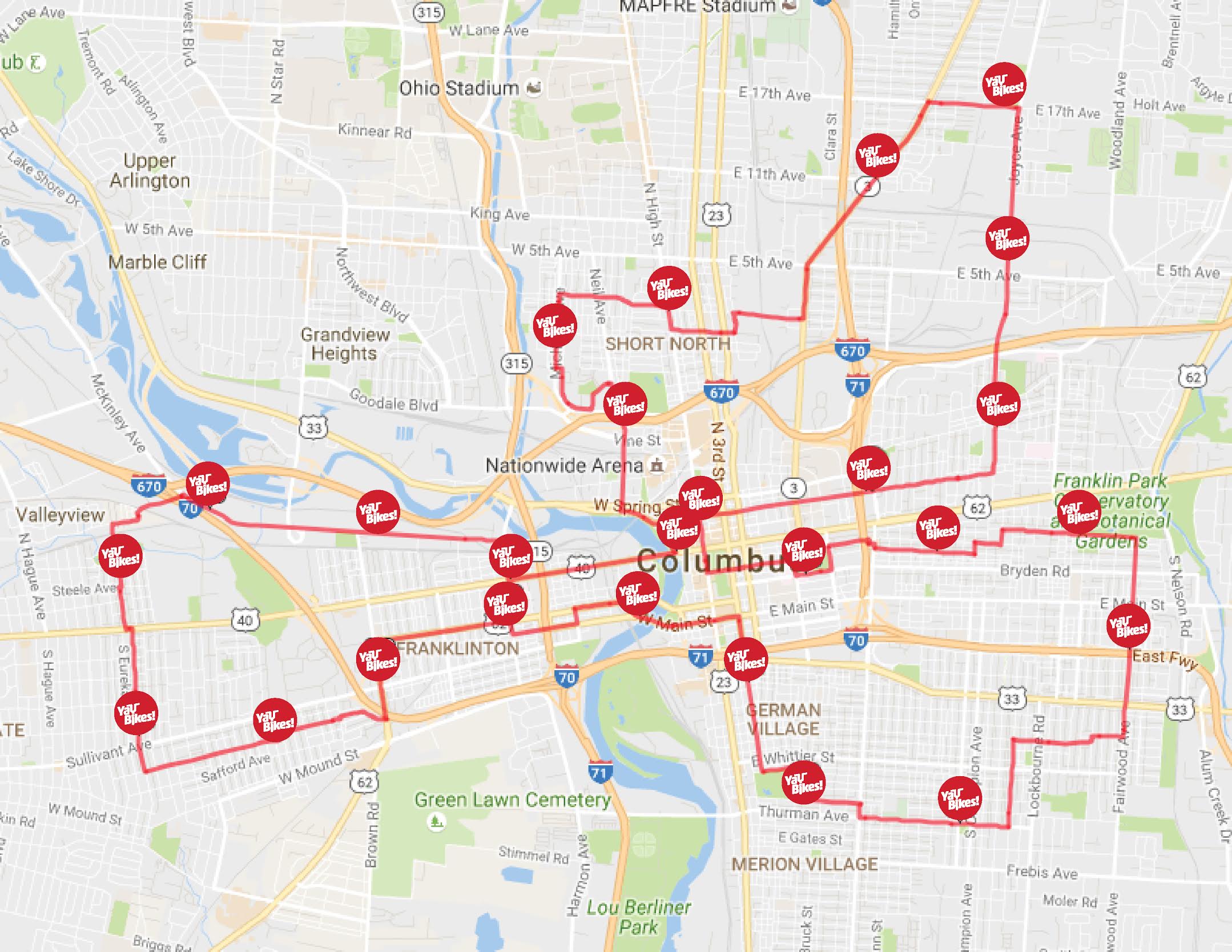

Draft 2016 route.

Big Reveal #2 NEW ROUTE!!! We'll be honoring our new mayor, Mayor Andrew Ginther, by highlighting his priority neighborhoods of the Hilltop and Linden for the first time. Our new route literally takes us to places we've never been before. We'll also browse through some of the love letters (bike infrastructure) written (constructed) by the fine folks at the Department of Public Service under the leadership of our new Director, Jennifer Gallagher. Yay Engineers!

Bike the Cbus, an urban ride in the tradition of Tour de Troit and Pedal PGH, is Columbus' oldest and only organized city-wide bicycle ride. On it, we highlight several inner-ring neighborhoods on a route totaling 25–30 miles (though you don't have to go the whole distance; there are several bail points). Last year we also launched Bike the Cbus+, an extremely unique, exclusively urban metric century ride that tours Franklin County. People said it couldn't be done, that it shouldn't be done, but we did it anyway. And it was GLORIOUS!

As with all things Yay Bikes!, Bike the Cbus has been designed to create an experience of place while acclimating cyclists to riding the roads. We want you to have an unparalleled experience of this city, and we want you to be on your bike for it. We want you to ride parts of this route again and again, because you'll know it leads to places you need to go—for work or childcare or worship or whatever—and places you want to go, simply because it's a joy to be on a bike in that part of town. This ride can make a cyclist of you!

Are you new to a ride like this? Don't be scared. The route is well marked, our rest stops explore neighborhood gems, mechanical stops are sponsored by local bike shops at multiple points throughout the route, and a couple of friendly folks "sweep" the route making sure no rider is left behind. Check out last year's photos and know you are going to have a wonderful day.

Are you an experienced rider looking for something a little different than the typical fitness ride? Bike the Cbus+ a metric century on city streets might be just the solution. This ride is led AND swept by well trained guides who know the route. They also know how to travel city streets with cars and will help you greatly expand your definition of a rideable road. Bike the Cbus+ travels in groups of 20(ish) people with the slowest group traveling at approximately 14 mph, and the quickest group traveling at 18 mph. This ride is SAG supported with 3 quick stops for nutrition, hydration, AND and indoor toilets. Yep, plumbing, sinks, air conditioning, the works.

REGISTRATION DEADLINE: Sunday, July 31, at 11:59pm, the cost to register for Bike the Cbus and Bike the Cbus+ will rise. And registrations Aug 1 and beyond DO NOT INCLUDE this beaut of a tee (though a limited number will be available for an additional fee of $15 each):

Our 2016 tee, designed by Jeremy Slagle of Slagle Design.

It's clear what you need to do: REGISTER NOW! This ride has the potential to utterly transform how you see Columbus and your place in it. Get. On. That. Bike. And. Ride. Bike. the. Cbus. (or. Bike. the. Cbus. +) There are also ample opportunities to volunteer—many of which allow you to also enjoy the rides and all of which provide you a free tee and an exclusive opportunity to join our pre-ride route vetting ride.

MORE NEWS